We are hearing from many senior leaders across industries, the need for organisations and the people in them, to become more nimble and adaptable. This is due to responding to market changes to remain competitive, keeping up with innovation in technology, and creating a culture where you are an employer of choice. With the current challenges in attracting and retaining the best people, organisations have to offer an employee experience (EX) that has people wanting to choose you over other enticing alternatives. The age of COVID has taught employees the value of working flexibly, to look for purpose and meaning in their work more than ever before and to think more deeply about work life balance.

None of this is news. What is required though are new ways of thinking about how to tackle these complex challenges that equates to both meeting the needs of your organisation and the needs of the people in it. Part of the solution lies in how we deal with complexity and changing trends.

I’ve recently had the opportunity to read the book ‘Team of Teams’ by Stanley McChrystal a former General in the US Army. McChrystal headed up the counter terrorism task force in Iraq from 2003. This involved 7000 people from different branches of the military, intelligence agencies and government. Despite having access to some of the highest funded infrastructure, resources, technology and know how in the world, insurgents were running rings around the might of the US. Through the use of social media, de-centralised planning and operations, and the ability to change tack quickly insurgents were succeeding in killing and injuring hundreds of people each month, with very few of them being caught.

The different departments and business units that made up the taskforce had no real experience of working together effectively. Special forces operators distrusted intelligence people and vice versa. Information wasn’t readily shared and that which was took too long to filter through to the right people. The organisation’s ability to respond to a changing environment was too slow.

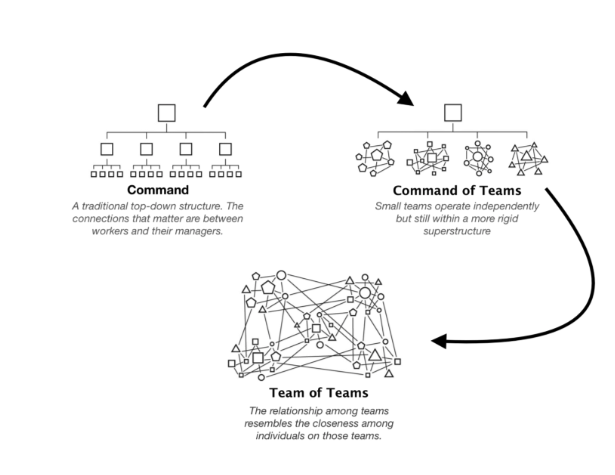

McChrystal came to realise that the traditional hierarchical way of working that characterised not only the US military and government, but also most organisations, could never succeed in a complex, fluid environment that required constant adaptation. McChrystal began to think about a different way the organisation needed to function. It needed to move away from a traditional hierarchical (or command) model. He implemented a model of highly effective teams (which he called ‘command of teams’), but found this was not enough. It only resulted in high performing silos. What was needed was a ‘team of teams’.

McChrystal passionately believes such ‘small team’ qualities as adaptability and resilience, can be achieved at scale. At its core, Team of Teams offers a new model for leading organisations. It argues that organisations can create an integrated, teaming-based model if they communicate with greater speed, inclusion, and transparency – and adjust their culture and leadership behaviour in conjunction with these process changes. At its core, in order to solve tomorrow’s challenges, creating a ‘team of teams’ is about moving from silos of information to shared consciousness of and across the organisation. This is coupled with team leaders needing to share more information and let team members make more decisions.

“I was most effective when I supervised processes – from intelligence operations to the prioritization of resources – ensuring that we avoided the silos or bureaucracy that doomed agility, rather than making individual operational decisions.” General Stanley McChrystal

In 2005 Alan Mulally took over as CEO of Ford Motor Company. He stepped into an organisation that was losing millions of dollars each month. It was rife with internal competitiveness. Engineers and designers saw each other as rivals, and a very real “us vs them” culture existed within the organisation creating strong silos. Mulally began by focusing on breaking down the internal competitiveness. He started a campaign he called ‘One Ford’ and set expectations around honesty and transparency. He recognised there were too many small meetings that created silos. He replaced them with a single corporate level weekly meeting, called the Business Plan Review. He got employees at lower levels involved in these meetings. He did work to integrate the designers and engineers. In 2009 GM and Chrysler. Ford’s two biggest competitors were filing for bankruptcy, whilst Ford had once again become profitable.

Building a team of teams

- Everyone doesn’t need to know everyone else on other teams that are interdependent with your team. Everyone just has to know at least one person on the other interdependent teams. Actively fostering these relationships is key. Having people that have worked in one team transfer to another team in order to enable this, is a strategy more organisations are leveraging. This can be done by either creating roles that are embedded or just liaison. The people assigned these roles need to be high performers with good emotional intelligence, otherwise they will struggle with the complexity and ambiguity of the role.

- Interdependent teams must agree on a shared purpose and goals that are common across the teams.

- Trust between teams is critical. Without it, real collaboration does not exist – getting key members of interdependent teams together to build trust is a must. These can be short sessions that focus on sharing and discussing conflicting priorities, clarifying expectations between the groups and getting to know each other.

- Creating transparency by making as much information as possible accessible across functions and levels. Both McChrystal and Mulally instituted regular large open meetings, that included hundreds of people. They shared information that previously would have been deemed too sensitive for people at lower levels to see. Transparency can also be enabled through – exposing your strategy to everyone e.g. using technology for strategy execution platforms, like Cascade, can help people at all levels connect to strategy and their part in it.

“According to the MIT Sloan Management Review, transparency trends are here to stay. And it’s not all because of millennials and Gen Z workers.

Expectations are rising across the board. Workers care about how the company operates. They want to understand more about its products and services. They expect leaders to capably field questions on all of the above.” Amanda Atkins, Head of Internal Communications, Slack

Traditional hierarchical organisations may not benefit from transition directly from a command-and-control structure to a team-of-teams structure. Establishing a command-of-teams or high performing team structure is an important intermediate step in success. For McChrystal, the separate teams quickly learned that sharing information was valuable to the mission and provided alignment in purpose. This step allowed trust to develop over time.

If you lead an organisation or head up the people and culture function an important first step might be discussing the 3 organisational models outlined at the executive level and aligning on a vision for the organisation centred around these.

If you lead a team a first step could be reaching out to the leader of another team that is interdependent in adding value to the organisation. Discuss what an alignment session could look like that enables building of trust, identifying issues and competing priorities, and aligning on some principles for working together even more effectively in the future. Just make sure you’ve done the work to build solid trust within your own team first!