What is a primary team?

Unless you are at the entry point of an organisation, you will most likely belong to two or more teams. For example, a maintenance supervisor will be a leader of her maintenance team and will also be a team member with other supervisors, and in a team reporting to a maintenance superintendent. In essence, a team leader whilst also being a team member.

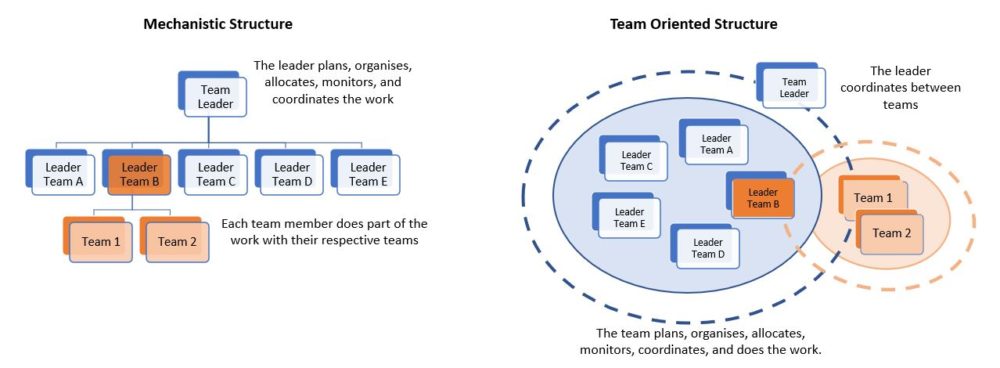

We can find this dual citizenship confusing at times, exacerbated by a number of factors including our rigid mechanistic organisational structures, bureaucratic reporting and communication flows, our time and energy allocation for each team, our decision making processes, as well as the psychological rewards and personal status associated with each team. It’s fair to say that the title ‘leader’ (and its other expressions) tends to invoke a greater sense of importance and worth than ‘team member’. This mental bias is hindering our progress towards a truly team-oriented approach to working in organisations.

Our bureaucratic-mechanistic organisational structure has worked well in simpler times, but has also allowed for hero leaders to flourish, silo thinking and behaviours to dominate, and stifled cross-departmental collaboration as well as information flow. In today’s less stable, VUCA environments this approach and its manifestations have been shown to severely hamper team performance.

So, as a team member and a team leader, which should be our primary team? The primary team is the team that deals with higher-level strategies, goals, problems, and key organisational issues or critical drivers of success. This team should get priority regarding meetings, decisions, and long-term strategy.

Characteristics of the primary team include:

- decision making is more difficult,

- agreed actions are broader and will impact multiple departments,

- problems are more convoluted with more antecedents and consequences, and

- transparency is critical which can expose shortcomings, which no one likes.

The Neuroscience

The position of team leader is bestowed with symbolisms such as title, higher remuneration, authority over the team and the power of veto over things like decision making and team activities. This feeds our sense of self-efficacy with a strong and reinforced perception of status, which is a powerful emotional domain. A strong feeling of status floods our neural receptors with the reward chemical dopamine that drives us to achieve even more. This is extremely powerful to our brains, with the dopamine rush being addictive and which can be difficult to negate.

Being a team leader also provides us with a strong sense of certainty, another strong emotional domain. The certainty that as the leader, orders and directions will be followed, also that ideas and solutions will be agreed upon and embraced by the team. It also provides a level of autonomy whereby a leader can make decisions for the team.

When it comes to time allocation, team leaders in general spend a greater amount of time with their functional teams than meeting with their peers. This can manifest into what’s known as distance bias, where we become closer and develop a greater sense of attachment. This is evident in the workplace when leaders give priority to team meetings over departmental meetings, or are not as present or engaging in meetings with peers. Also, leaders can develop a safety bias, where they can be very defensive of the team they lead, and protective towards criticism or scrutiny from outside influencers. When leaders are most interested in the interests of their own team, it leads to ‘silo thinking’, and the sensation of needing to be the “hero leader”.

On the other hand, being a team member (even of the primary team) is often considered less significant, especially if all members are considered equal. There is less certainty as ideas can be more easily challenged or dismissed, possibly resulting in the same sensation as of being attacked. This can put the brain in a stressed state, releasing adrenaline and cortisol, resulting in instinctive fight or flight behaviours. Have you ever seen leaders push back hard and defend decisions or actions even when everyone else disagrees? As a result, the interest in the “bigger goal” of the organisation is neglected and integrated cooperation between the different functions or teams will deteriorate.

Embracing the primary team concept

It all starts with the leader and their leadership shadow (what you do, say, focus on, and measure).

As team members of their primary team, leaders need to be moved into a different mindset, which means overcoming their biases and natural emotional responses. The work of the team leader and the team becomes the task for the team as a whole. The team leader becomes the boundary rider, managing coordination outside the team, between leaders of other teams.

In structure, the teams shift as shown in the figures below, which are quite different. Team leader and team member roles and responsibilities change substantially from one to the other. The required skills also change and that’s why this shift is more difficult than people anticipate.

Here are 5 key tips to help leaders facilitate the shift between teams:

- Explain the concept of the primary team clearly and link its importance with the strategic goals of the organisation.

- Promote that primary team thinking aligns with systems thinking (see the sum instead of only the parts) and leads to integrated planning. This benefits the whole organisation rather than a piecemeal approach that oils the squeakiest wheel.

- Emphasise the importance of teamwork and cooperation. Make sure your team members know what is expected from them and what will not be tolerated.

- Measure primary team performance separate to function or individual team performance. Pick KPIs which are the aggregated result of the sum of the parts. Avoid (unhealthy) internal competition and (only) personal performance indicators. Let the best in class help the others succeed.

- Reward integrated (between teams, departments, divisions, …) improvement initiatives, best practice sharing, and other whole of team behaviour.

Taking up these tips will underpin the development of high-performing teams and long-term organisational success.