The confidence and capability gap in modern workplaces

- Dunning Kruger Effect

- Cognitive bias

- Personal awareness

- Ineffective leadership

Susan is a mid-level manager leading a team of six. She ticks all the requirements of her role, such as annual performance reviews, weekly team meetings and allocating day-to-day tasks, to name a few. However, at best her team’s performance is mediocre. They often miss obvious opportunities to value add when completing tasks, rarely challenge each other, give each other little feedback and have fallen into a constant routine, with no workplace improvement initiatives or projects.

However, team performance is not the only issue here. During Susan’s performance appraisal with her manager she was totally convinced that her performance as team leader was exceptional and gave herself high ratings across her performance criteria. No matter what her line manager said Susan was convinced and totally confident that she was a great team leader.

Unfortunately, Susan’s story is not an isolated case. Even on the world stage we see this phenomenon being played out at the highest level of leadership. Leaders who believe that are better than what the case really is. What we are really talking about is the confident and competent gap, in leadership.

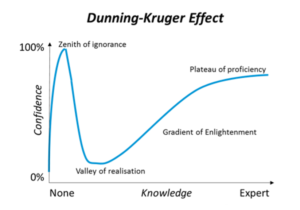

In the field of psychology, the difficulties experienced when assessing one’s own competence is known as the Dunning–Kruger Effect (1999). This is when our low self-awareness and cognitive bias result in illusory superiority, and we mistakenly assess our ability as greater than it is. This cognitive bias of illusory superiority comes from our metacognitive inability to be hyper-self-aware, therefore we cannot objectively evaluate our actual competence or incompetence.

Over the years, numerous studies have shown that examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect are everywhere. In our organisations where workers continually over-rate themselves, on our roads where drivers often rate their skills as above average, and students who continually over-state their performance grades.

One of the problems underpinning the Dunning-Kruger Effect is that many people who are overly confident yet still manage to under-perform do so because they don’t know that they could be doing better or what really great performance looks like. It’s not that they are inevitably being defensive, rather they just lack deep self-awareness and knowledge.

The Dunning Kruger Effect notes that, for a given skill, incompetent people:

- Overestimate their personal skill level.

- Fail to recognise genuine skill in others.

- Fail to recognise the extent of their incompetence.

- Can acknowledge their own lack of skill, if exposed to training in the skill tested.

Interestingly the Dunning-Kruger Effect is also mirrored in highly competent individuals who may erroneously assume that tasks easy for them to perform are also easy for others to perform, or that others will have a similar understanding of subjects in which they themselves are well-versed.

The cognitive states related to the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is then manifested through a lack of self-awareness, causing an illusionary perception of confidence without necessarily knowing or understanding the competency requirements associated with success. So why is it so hard to be self-aware and so easy to be ignorant?

Relly Nadler (Psychologist, Master Certified Coach and author of Leading with Emotional Intelligence) claims there are a number of reasons why we can be so mistaken:

- Intention and execution gap: We may have 100% intentions and only 50% effective skills in carrying out our intentions.

- Introspection illusion: Introspection feels as if we have uncovered our true intentions, when in reality we are making educated guesses about our intentions, many of which are unconscious.

- Our thoughts are facts fallacy: Thinking something and totally believing it must be true and don’t check your assumptions with others and worse act only on limited or skewed data.

- Lack of feedback: In organisations there is a scarcity of meaningful feedback that is candid, accurate and actionable.

- Leaders don’t ask for feedback: It is uncomfortable for leaders to ask for feedback about their performance from others, thus miss knowing more about themselves.

- Superiority illusion: We overestimate our strengths. We think we are more successful, interesting, attractive, and friendly than the average person. Tali Sharot reports 70% of leaders rank themselves in the top 50%.

- Underestimation of negative impact on others: Leaders minimise their influence on others and usually don’t hear about the times when people are upset with their actions or behaviours.

- Our memory distorts reality: We create false attributions and stories about the facts of a situation.

With over 20 years’ experience talking to leaders and teams these factors seem more prevalent today than in the past. Possibly through the information boom of the internet where information on almost anything is available with just a couple of clicks, the rhetoric of leadership is easier. Also, the speed of change has seen an increased pace in promotion and a wider spread of opportunities, with job hopping being common. A friend recently said to me, “all I want is someone who can do their job, someone who is competent.”

What does this mean for workplace leaders – like Susan? And what can be done?

As a starting point, our self-awareness has to be developed and practiced. David Rock (Neuro-leadership) reports that almost 50% of the time we are operating on automatic or not consciously aware of what we are doing. In the Goleman, Boyatzis, Hay Group EI model Emotional Self-Awareness is defined as a leader who recognises feelings and how they affect them and their job performance. So, it is identification of the emotions, implication of that emotion on your performance, which then gives you the ability to manage or alter your actions. Time for reflection and intensity of feedback is critical.

The Competent Leader

If confidence has little certainty when determining a leader’s competence, what characteristics of a leader may indicate a better measure of competence or at least the likelihood that this leader is not suffering from an overestimation of abilities? These three characteristics may assist:

· Awareness of Personal Strengths and Weaknesses

To avoid the Dunning-Kruger Effect, a leader must be continually evaluating their strengths and weaknesses. No leader has all the answers and the world is constantly changing. Many competent leaders are aware of this fact. They know their blind spots, remember mistakes and learn from them. They understand their level of skill and/or knowledge and take positive steps to improve. Continuous feedback, coaching, behaviour assessment tools and leadership development programs can help.

· Ability to See, Listen and Feel

Competent leaders develop their social awareness skills. For example, active and empathic listeners have the ability to listen intuitively to someone’s conversation while evaluating its true depth and meaning. The empathic listener, listens to discover “how does this person feel – how can I help them?”

As a very wise friend once said, “you need to be able to see what’s not there, hear what’s not said and smell and feel the air as you walk into a room.”

Highly ‘social intelligent’ leaders are the new frontier for progressive organisations.

· Ability to Use Constructive Feedback

Ask for constructive feedback from anyone as often as appropriate: co-workers, subordinates, customers, and even friends. Ask that it be unfiltered and honest. Each piece of constructive feedback allows for self-reflection, personal growth and deeper self-awareness. Being vulnerable and honest is the new norm, faking it till you make it, is obsolete.

So, Let’s Eradicate the Over-Confidence Epidemic by Improving Competence

The three aspects of competence above involve highly developed reflective skills as well as external sources of information, which help inform your internal self-assessment. They provide the balance of subjectivity and objectivity you need to continue along the path of competent leadership and avoid the subjective pitfalls of the Dunning-Kruger Effect.